Working for a Criminal in the Shadow of Fat Leonard

So there I was, standing at the head of Reactor Training Classroom One aboard USS George Washington. My carefree days of non-qual Tuesdays were distant memories, and I had not only qualified as a Propulsion Plant Watch Officer, but been assigned to Reactor Laboratories Division, leading two dozen Engineering Laboratory Technicians (ELTs) whose duties included drawing off and analyzing water samples the propulsion plant, performing radiation surveys all about the ship, and making logs of the same. My job? Well, my job was to tell my Leading Chief Petty Officer to tell the ELTs to keep on doing all of that, and to review all the logs (but only after three other people had reviewed them ahead of me and signed off that they were good) before dutifully passing the very same off to the Chemistry and Radiological Assistant (a Lieutenant Commander and my immediate superior) for final review and approval. I was a regular middle manager!

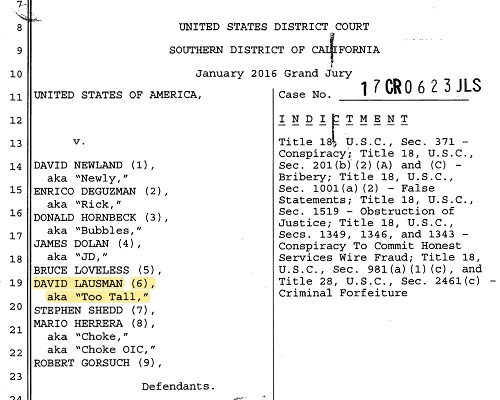

But on that fateful day in the reactor training classroom, with my newly established bona fides in all things chemistry and radiological, I was giving a lecture to the other Watch Officer/Watch Supervisor-qualified members of the crew (most of the officers and chiefs in Reactor Department, plus a few assigned elsewhere, and a handful of First Class Petty Officers), when, lo and behold, the ship’s top nuke appeared: our newly-appointed Commanding Officer, one David A. Lausman, aka “Too Tall,” formerly Commanding Officer of Seventh Fleet’s flagship, USS Blue Ridge, but, as of posting, more widely (and infamously) known for his criminal1 activities in relation to Malaysian defense contractor Leonard Glenn Francis’ years-long corruption and bribery scheme.

Anyway, it was my first encounter with Lausman, I was still a Lieutenant Junior Grade at the time, and I was giving a lecture on propulsion plant chemistry to a room full of officers and senior enlisted. Well, accept there was this one much more junior sailor, a Third Class Petty Officer, in the back. I mean way, way, waaaaaay in the back. How far in the back? So far that he wasn’t even in the classroom, just visible from it. You see, we were in port at the time, only about two-thirds of the way through a period of maintenance and overhaul which included phase one of what would be a multi-step and multi-year modification to and rearrangement of the reactor training spaces. At that particular moment the classroom was usable, but a false bulkhead that normally sub-divided a larger compartment to make two classrooms had been removed, and so it was possible, while the modification was ongoing, to see, from Reactor Training Classroom One, where I was my lecture, into what had been a separate, adjacent classroom (Reactor Training Classroom Two). Reactor Training Classroom Two is where the newest sailors (like this Third Class Petty Officer) were allowed to go and study (because they still hadn’t been assigned to a division, so they had no divisional office to go to, the propulsion plant itself doesn’t have anywhere to sit down–at least not officially–and of course everything they had to study was classified, so it’s not like they could do their studying on the mess decks). So, in a sense, this young petty officer, being merely visible from my position, was “in the classroom” to the same extent a the Moon is set upon the Earth. I mean, you can see one from the other and vice versa, but they aren’t the same, you know?

Why I have spent so much time belaboring this point? Well, because no sooner had Lausman walked in than he stopped, craned around to his left, and looked through the opening between the classrooms to this young petty officer just sitting there, minding his own business and studying while listening to an MP3-player with headphones on (as was allowed to do at the time–I suppose now I’m not sure what the current policy is on Mp3 players in secure spaces).

Lausman, on seeing this young petty officer sitting way way waaaaaaay in the back listening to music and not paying attention to the lecture (because why would he?), became apoplectic. He immediately launched an instant tirade. A real fire-breathing, get ’em up against the wall tirade of the sort that I have not seen outside of that scene in Catch-22 and that one time a sailor assigned to USS Kitty Hawk murdered a middle-aged Japanese woman for subway fare and the Commodore came over to my ship (which was most definitely not USS Kitty Hawk to bitch us out over a… much less serious incident–but still way more serious than listening to an MP3 player while studying in view of a lecture). Anyway, once Lausman finally regained his powers of locomotion (beyond just gesticulating and shouting, I mean–enough to walk), he stormed on over to this young petty officer, demanded that he hand over his MP3-player (which the petty officer promptly did, most sheepishly), and then bloviated some more about how, unless this petty officer knew everything there was about nuclear power, he should be paying attention to the lecture and should expect to see him again at Captain’s Mast. “I’ll be seeing you again! You will lose privileges over this!” were his exact words on that point–but of course he kept going. It was just… biazarre.

Mere seconds after Lausman began his embarrassing tirade, the Reactor Officer, who had been attending the training as well and was himself a Captain by rank, was at Lausman’s side, trying as best he could to get Lausman’s attention and interject for a moment–just a moment–to explain what was going on, to lay out the facts out for Lausman and explain that it was all just a misunderstanding, that this poor, most junior petty officer was not actually “at” the training–nor was he even supposed to be–and that this training was only for qualified Watch Officers and Watch Supervisors. To explain, as I have already explained here, that this petty officer was in fact studying in an adjacent classroom, not skipping out on training, and that not only was he not doing anything wrong, he was actually doing exactly what he was supposed to be doing at that moment.

But it was some minutes before Lausman paid any attention to the Reactor Officer, and the scene remains as close as I have come to seeing Captain Queeg’s infamous tirade from The Caine Mutiny (1954) play out in real life…

…except Lausman’s rant was louder and more unhinged, and he didn’t even bother to direct his fury at any the officers in the room. He just kept right on laying into the junior sailor.

Eventually, the Reactor Officer managed to get Lausman’s attention and explain the situation. Lausman calmed down enough to turn away from the petty officer and take his seat (to watch the training I was giving! remember that? This started with me giving a lecture on propulsion plant chemistry, in case you’ve forgotten). Anyway, at the end of the lecture, Lausman signed off on the training monitoring form (every training is supposed to be monitored with written feedback provided) and rated me as “Below Average,” with the “Above Average” the Reactor Training Assistant (the Lieutenant Commander in charge of training, and also in the half of Reactor Department officers who had Lausman’s sorry affair) had initially circled being scratched out by Lausman’s own hand, because–according to Lausman’s own scrawl in the comments, I had “misspelled [the name of a chemical that helps maintain pH for the steam generating system]” and demonstrated “poor classroom control” (for not lighting up that petty officer who wasn’t even in the classroom). From that first encounter to the present day, Lausman remains the most un-Captainly Captain I’ve ever met, and, dammit, I’ve met met Captain Graf.2

The next time I interacted with Lausman was at my promotion ceremony, from Lieutenant Junior Grade to Lieutenant (Fleet Lieutenant! as one of my fellow promotees would insist), held June 1, 2009. Lausman showed up ten minutes late (no judgment from me on that account–a ship’s Commanding Officer has a busy schedule, especially as we were at sea), but then assumed that someone else had already promoted the lot of us in his absence. No sooner than he arrived, and without inquiring into the actual situation (a kind of theme with him), he clapped his hands together and said “Congratulations to our newest Lieutenant Junior Grades!” whereupon, after an awkward moment where Lausman was the only one clapping, the Reactor Officer whispered into Lausman’s ear something to the effect of “Actually, Captain, they’re all being promoted from JG to Lieutenant. We were waiting for you…” The Reactor Officer then motioned to our Lieutenant’s bars, still laid out on the table atop accompanying (unsigned) letters of appointment. Lausman then strode, most awkwardly, towards the table, but tripped just short. In the act of catching himself, he hit the table with enough force to send our rank insignia flying off, clattering to the deck. And that is why, from that moment on, I was cursed: because my rank insignia touched the deck before I ever wore it. It’s just like Apollo 13, where someone dropped an oxygen tank on the deck more than a year before the mission ever launched, and everything went to hell as a result. It’s why I ended up in Iraq, it’s why, when I asked for orders to San Diego, I got Bahrain instead, and it’s why my naval career ended prematurely in a medical retirement: because Captain Lausman let me down. It’s why I don’t believe in nothin’ no more, and it’s probably even why I went to law school.

But let’s move on! After all, this is supposed to be a retrospective on a WestPac deployment, not a prolonged meditation on every toxic-leader-turned-criminal I ever served under.

Crossing the Line

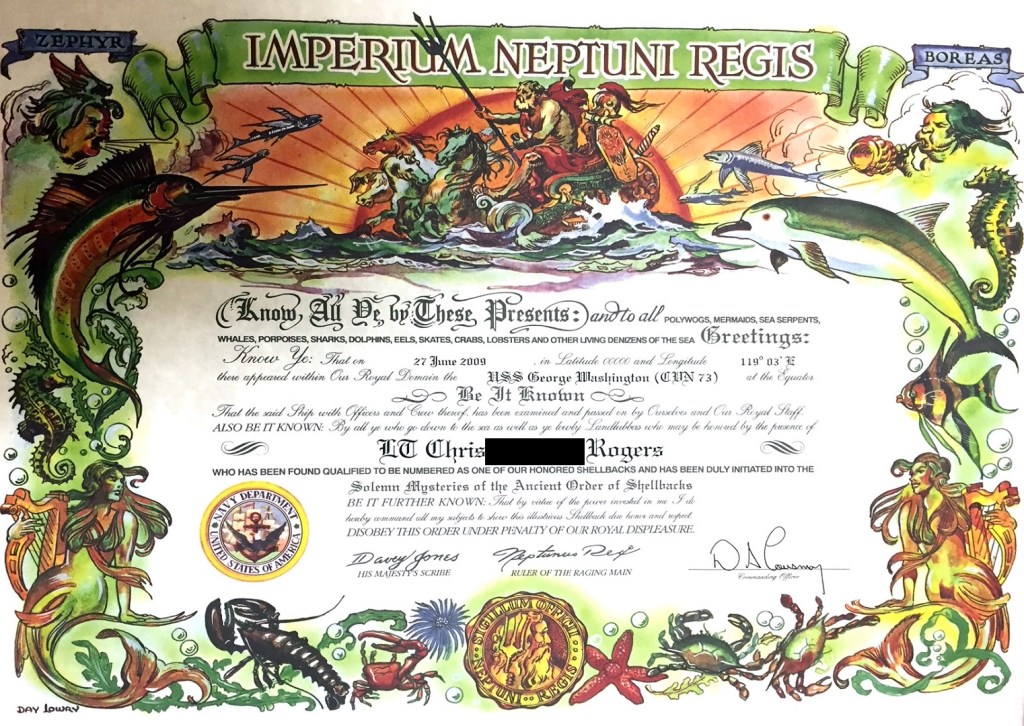

I want to be very clear: I am not a crook, nor am I a pollywog. What that means is, not only have I gone my whole life without betraying the trust of the American people (such as by accepting bribes in exchange for official act or forbearance), I have in fact crossed the line and been duly inducted into King Neptune’s court as a trusty shellback. Read it an weep, landlubbers!

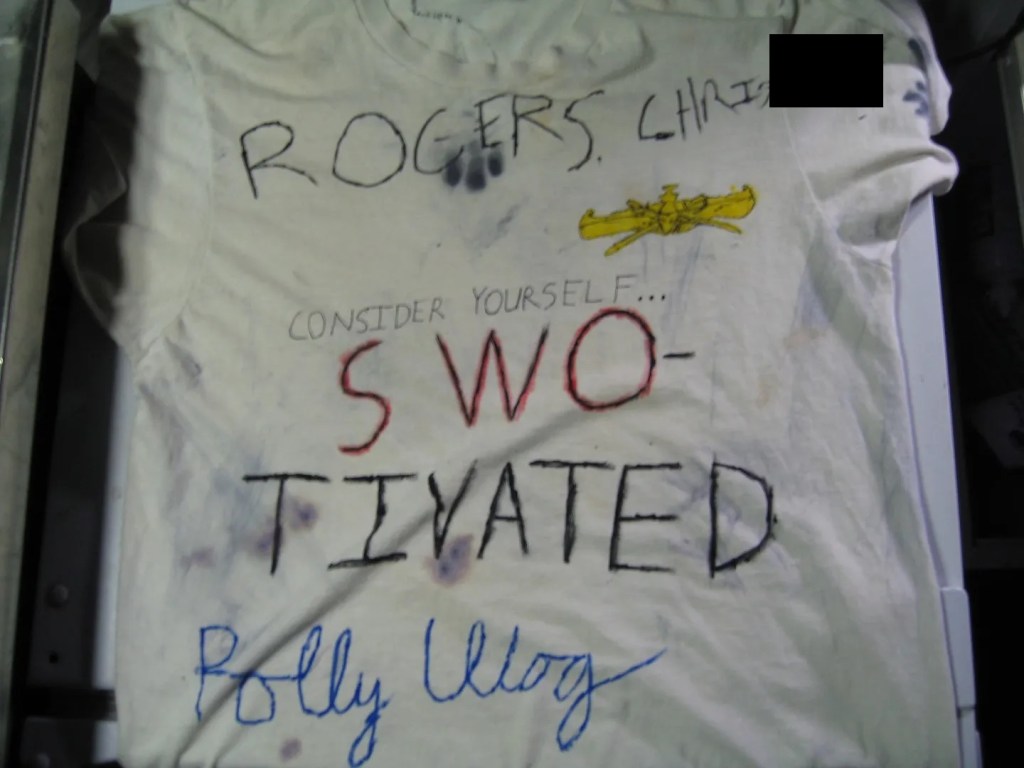

…although, on close examination, it occurs to me the authenticity of this document might be questioned, seeing as one of the signatories is a man of known ill-repute (here referring to Lausman–and trust me, this will definitely, totally be the last thing I have to say about Lausman. Honest.), who smeared the sacred parchment by affixing his name at bottom right (and not at my request, of that I can assure you). Therefore, as further proof of my bona fides, I have included below a picture of the shirt I wore as I proceeded through the solemn and sundry rites of induction into His Sacred and Most Exceptionally Nautical court:

As you can see, this was an off-white T-shirt of ringspun cotton cloth of a kind most durable, marked and anointed with some of the finest dyes and oils (having previously served as a shoe-shine rag on account of having a tear along the back collar, only faintly visible at top, just to the left of center, and which a keen eye will note was handily mended to allow Neptune His due respect). You will also note the Surface Warfare Officer insignia positioned such as to be above the wearer’s left breast, and the exquisite cursive handwriting–this author’s very own–indicating the unambiguous authenticity of the whole garment. Seriously, this is the kind of thing you cannot fabricate, even though I did just literally admit to making the whole thing up out of a dirty rag and some markers, probably over the course of, at most, five minutes.

With my status as shellback thus established according to the most rigorous of proofs, we may now proceed into the southern hemisphere and on to terra australis without fear of reproach or revengeaning (recall the preceding year’s fire, which an official investigation determined was “entirely preventable,” if only the ship’s leadership had offered the appropriate rites before intruding upon His Domain).

Why were we heading south? Hell if I know. Some exercise, I think–Talisman Saber maybe? Unlike my first two deployments aboard a destroyer, on the carrier I didn’t really have a clear sense of what the ship was doing day to day. I mean, it’s often said that the biggest difference between being a nuke on a submarine and a nuke on a CVN is that on a CVN you get to see the sun every now and then, but that was not my experience at all. I slept on the 2nd deck, I ate on the 2nd deck, my division–and indeed almost all of Reactor Department–had its office on the second deck, I attended training on the third deck, and I stood watch on the fourth deck and below (for those who are not aware, floors, or “decks” in Navy parlance, below the first/main deck get higher in number as they go they go lower down in the ship, not unlike the Nine Circles of Hell). Point being, if the ship wasn’t in port, I had no cause to be above the second deck, and so for all intents and purposes I might as well have been under water–but without a periscope.

But I did at least know where we were going to end up eventually, whatever we did along the way, and I was looking forward to it: we had a port visit in Australia scheduled around July 4th.

The Port Visits

1. Freemantle and Perth.

Okay, actually, before we “go ashore” in Australia, there’s something more I want to say about Lausman (and here, I confess, that for all my earlier protestations to the contrary, even this will not be my last word on Lausman). To set the stage, I’ll note that the US Navy’s nuclear propulsion program maintains very high standards of training for all nuclear-qualified sailors at all times, whether the ship is out on deployment, as we were, or in drydock (when there is actually more time devoted to training, which totally sucks, and I know that because my last real job in the Navy was taking the very same ship, USS George Washington, into the yards for refueling–it was in fact the job that finally broke me, though perhaps only in a “straw that broke the camel’s back” sort of way). Point being, nukes are always training in addition to operating and maintaining the propulsion plant around the clock. As part of that training regimen, nuclear-qualified watchstanders of all ranks are regularly tested to verify not only their individual ability to retain and apply their knowledge of the propulsion plant (to include underlying theory, such as Reactor Dynamics questions waaaaay more advanced than this stuff).

That all sounds nice, doesn’t it? Trouble is, it’s kind of tough to operationalize that. I mean, it seems like ought to be really simple: just print out some questions from a bank, sit every sailor down in a room, have them take their exam, and then grade those exams according to a key which must surely be provided. Trouble is, that’s not how the Navy has chosen to handle these problems. Leaving aside the practical problems of being unable to get all the nukes in a room at the same time (even if there were a compartment big enough to hold so many people at once–there are a couple on a CVN–someone still has to be operating the propulsion plant), there is the more fundamental challenge of generating the exams. Because each ship is unique,3 the Navy has decided that it would be impractical, maybe even dangerous, to just have one centraized organization generate questions and answers for every nuclear powered vessel, or even every nuclear powered aircraft carrier, in the Navy. Instead, that task is left to each individual ship’s training establishment: every single exam administered on the ship (and these are not multiple choice, or even single-line short answer exams: the questions are supposed to test understanding, not merely retention after all) must be created essentially from scratch by that ship’s training staff. Every single exam is, for the nuclear training staff, a major evolution from generation to administration to grading to analyzing to reporting to remediating and it’s by far not the only job the training staff has (there’s also maintaining and auditing qualification records, training new sailors, coordinating lectures and seminars, and, perhaps most taxing of all, running frequent casualty control drills on a pair of operational nuclear reactors–and that’s by no means an exhaustive list). Point being, it’s kind of hard.

In theory, the exams are not only a check on each individual sailor’s ability to retain, understand, and imply important concepts, they are a means of evaluating the effectiveness of the training program (and the training staff) itself. But of course that seems awfully circular, doesn’t it? The same people who design the training program are supposed to be relied upon to test their own effectiveness with exams that they themselves must write, administer, and grade?

Well, yeah, it kind of is. Of course the Navy sends outside entities to inspect ships and their reactor departments from time to time, and there is an examination component to such inspections, but a lot of what the inspectors look for is how the department (and specifically its training staff) has graded itself. The trick, therefore, is for the training staff to show that it has administered sufficiently rigorous or “hard” exams by not having average exam scores that are too high, while also showing that the department (and by extension the training program and training staff) is doing “well enough” by not having average exam scores that are too low. Where, for example, the minimum passing score is a 2.8 on a 4.0-scale, you’d probably want the department’s average on any given exam to be well above a 2.8 (because, assuming a normal distribution, if the average is a 2.8, then that means about half the department failed the exam, and that can’t possibly be a good thing, can it?). But, again, if the average score is too high (and god forbid nobody failed!), then that really brings into question just how rigorous the examination process is. Surely, think the inspectors, it can’t just be that the department did so well because the training program is just so effective that no one failed a legitimately hard exam.

What this all boils down to is that if the average score on exam is outside the 3.0 to 3.2 range, then somehow, some way, the training staff must have screwed up–or at least that’s the presumption the inspectors will make, and good luck rebutting it between drills sets, RTA. So, naturally, the incentive for ship’s training staff is to “massage” things to get a department’s average on any given exam to somewhere in the 3.0 to 3.2 range, such as by practically giving away roughly two thirds of the points, another ten to twenty percent on things most people would know, and awarding the last few points for things that no one in their right mind would actually have memorized (oh, did I say memorized? I meant “understood with perfect recall”). Done correctly, this gets the department a nice, tight grouping in the 3.0- to 3.2-range that could earn the RTA another oak leaf cluster gold star on their Air Navy Achievement Medal. Too bad that incentivizing training programs to devote time and energy to making sure the metrics look good instead of, you know, training people, doesn’t lead to improved training and readiness, only improved metrics.

But what’s the point of all this? Why am I going into such excruciating detail on the intricacies of grading nuclear exams? Because the context is critical to understanding a certain decree Lausman made en route to Australia. So it really does relate to the port visit I’m supposed to be writing about, in a round about way.

For some additional context–no more on exam-grading, at least–there were a number of cheating scandals and other lapses in integrity involving nuclear engineers aboard aircraft carriers and submarines around that time (circa 2009). Some of these “scandals and other lapses” even made the news (which is a big deal considering how much of the information surrounding the naval nuclear propulsion program is supposed to be classified). Careers were cut short and, in many cases, probably lives ruined. Because unlike high school or civilian colleges, where cheating on an exam gets you an F on the exam, or maybe (if the school is really strict) an F for the course, cheating in the Navy is punishable under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. And where nuclear engineers, in particular, are involved, cheating and other lapses in integrity (such as fabricating records or falsifying logs) is guaranteed to result in Captain’s Mast regardless of rank, a career-ending letter of reprimand for any officer involved, a reduction in rate for any enlisted sailors (plus restriction, and probably extra duty and loss of pay above and beyond the reduction in rate as well), and somewhere in the range of 50/50-odds for getting kicked out of the nuclear program (for enlisted sailors–officers will be sent packing, guaranteed). See, for example, Report: Cheating found on aircraft carrier (from February of 2009).

As for the Reactor Officer? Well, even if they didn’t sanction the cheating and responded appropriately once it was uncovered, questions are sure to be raised about their leadership abilities for not uncovering it sooner. If they were found to be negligent in providing oversight or, worse, to have imposed a “zero defect mentality” (as if that’s a bad thing for the nuclear Navy?) and presided over a “culture of fear” such that the consequences for an honest failure were extreme and excessive, their career could be over too (and to be clear, even the ordinary consequences of failure in the nuclear Navy were nothing to shrug at, with a range of options starting at additional hours of study and remediation on top of regular watchstanding and maintenance duties for a first-time failure, with yet more hours of extra study for repeat failures, and the possibility of loss of supervisory qualifications and associated pay or even a total loss of nuclear qualification following multiple failures).

So it was, returning to Lausman and USS George Washington‘s southward voyage to Australia, in the context of all I have just described about the need to carefully curate exams to achieve a particular range of scores that both allowed the bulk of the department to pass while also not allowing too many people to score too high, and in the broader context of a string of cheating scandals on other vessels, that Lausman issued the following decree:

There are only two possible grades as far as I am concerned: Excellent and Not. A barely passing score is not excellent. Therefore, any sailor who scores less than a 3.0 on the [upcoming very important] exam will be denied liberty in Australia and will be assigned extra study hours for the port visit instead.

Lausman, aboard USS George Washington, en route Australia, circa June 2009

That’s not an exact quote, but pretty close (and I will always remember how he pronounced Not like Naught). But more important than his exact words, his precise manner of speaking, or his particular dialect, is what sailors actually heard: that was, “Cheat, or else you’re on restriction.” Obviously Lausman didn’t mean to say exactly that, but that was the only way to achieve his desired result, and in a way it was a kind of perverse reflection of how orders are supposed to work: a superior tells their subordinates what to do, and then the capable subordinate determines how to do it. The Captain wants everyone to get a 3.0 or better on the next exam? Okay, let’s all cheat! Or such was the prevailing mood.

While I could cite this incident as yet another example of Lausman channeling Queeg from The Caine Mutiny (there’s a line that goes “Aboard my ship, excellent performance is standard, standard performance is sub-standard, and sub-standard performance is not permitted to exist”) I don’t think that’s fair–to Queeg. Queeg, you see, was suffering from what we might now call PTSD, whereas Lausman… honestly, I don’t know what his deal was, only that while he was laying out these bordering-on-the-mathematically-impossible goals for us, he himself had already (allegedly, according to the DOJ’s original indictment, which I consider to be credible even as I recognize Lausman’s conviction was vacated and he has since pled guilty to a lesser charge) committed a number of felonies related to corruption and bribery, we just didn’t know it yet. So, in light of the seeming obliviousness of his remarks, such that I might might reasonably call him “obtuse,” coupled with the (alleged) acts of corruption and bribery that have since come to light, I think Shawshank Redemption‘s Warden Norton serves as a more appropriate point of comparison. Bonus points because Lausman, like Norton, presented himself as a beacon of rectitude and righteousness while absolutely crushing anyone who stepped out of line (we’ll get to that shortly).

And, also not unlike Shawshank’s Warden, it’s just possible Lausman wasn’t so oblivious, so obtuse, as he seemed: by this point in the deployment, Lausman had already been overheard talking, in front of junior sailors even, about how much he hated nukes. How he thought nukes were overpaid and spoiled. Where most people would look at the extensive retention and reenlistment bonuses available to nuke officers and enlisted and think “Gosh, nuke life must really suck for the Navy to be willing to pay so much money to keep them around,” Lausman’s position (and here again this is not an exact quote, but pretty damn close–and certainly it’s how he acted) was, “Nukes are the most spoiled, entitled, and overpaid sailors in the Navy, and I’m going to make them work to earn their pay.” As if there wasn’t enough work already to be done. All that to say, maybe it not only occurred to Lausman that his unrealistic standards would absolutely destroy the morale (and possibly the integrity) of the Reactor Department, but that was in fact his specific intent. Whether the outcome was half the department spending the entire deployment on the ship for the offense of achieving merely passing scores on their exams, or taking dozens of sailors to mast for cheating, it’s just possible he’d have been okay with that, perhaps even wanted it.

Fortunately, the Reactor Officer, who recall was himself a Captain and not exactly a pushover, was not so eager to Kobayashi Maru the next set of exams. Whether he through direct appeals to the Lausman, or through subtle hints prompting the strike group and/or the Type Commander to make a “suggestion,” Lausman rescinded his mandate.

So we finally made it to Australia.

I regret to report that I did not take many pictures of Australia (though it was quite lovely, especially considering that it was early July, and so supposedly the dead of winter for that part of the world), but here’s a couple from Freemantle, which is a modestly-sized town on Australia’s west coast, where we anchored out:

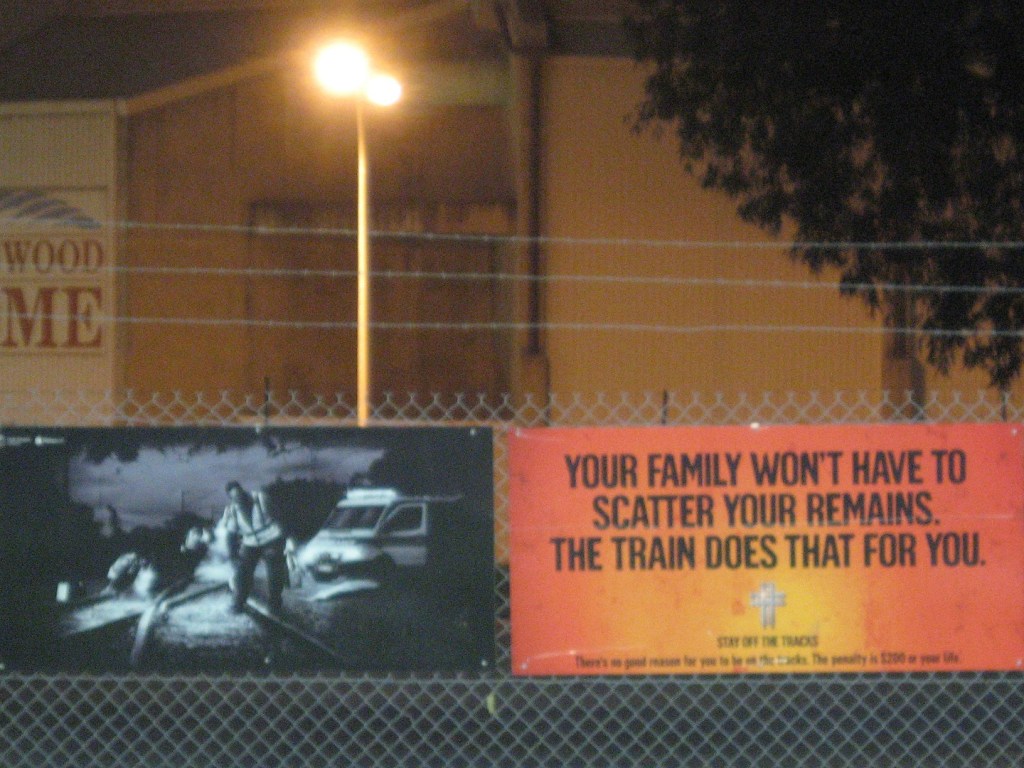

However, we were close enough to Perth to get there via a short train ride, and that’s where many of us spent the port visit. Unfortunately, I got even fewer pictures there, with the most prominent being one I took of the operating hours for the Kings Square Toilets (I’ll spare you the actual picture. I only took it because I thought it was funny that toilets would have operating hours–from 9 AM to 5 PM, to be exact), plus this somewhat blurred picture I took of a public service announcement at the train station:

Aside from that, the only notable thing that happened in Australia was that I gambled at a casino (they have casinos in Perth) for the first and only time in my life. Two rounds of roulette, 20 dollars on red each time, and I won both times. With a record like that, you really should be sending me all your money. I mean, statistics don’t lie. Who else can you name that has a 100% perfect gambling record?

But, yeah, other than that, nothing remarkable happened in Australia and I had a nice, relaxing time. Just chilling on the Fourth of July with five thousand of my closest friends.

Oh, and one of my first class petty officers got drunk during an MWR-sponsored tour (a “wine and song” tour, go figure), got into a cab with his liberty buddy bound for their hotel room, but then spontaneously got out of the cab, abandoning his liberty buddy at a red light, and went on to get even drunker at a series of bars before managing to get himself arrested by the local police. But of course that was not the end of it. While in the back of the police car, his hands cuffed behind his back, he managed to extract the shaving cream from his overnight pack and smear it all over the interior. Then, after some hours spent detoxifying in a holding cell, and just as the police officers were extracting him from the cell to hand him over to US Navy shore patrol, well… his version of events is that one of the Australian police officers pulled him forward, causing him deliberately to stumble into the officer, with the officer then falling back to the floor without letting go and essentially drawing him down on top of the officer. A real comedy of errors. And you know what? Not knowing this particular police officer and how he felt about tourists and/or US Navy sailors… who am I to say that’s not exactly how it went down, either as an accident or as an intentional pull by the officer to make it look like this petty officer (who, again, had just smeared shaving cream all over the back of a squad car–maybe even his squad car) was assaulting him? And, heck, for what it’s worth, this particular petty officer was known to me, both before and after the incident, as a trustworthy and reliable individual who had held positions of leadership within the division and would likely have promoted to Chief Petty Officer inside of a year or two, but for this sad series of events. With that, I was and am, to this day, inclined to give him as much benefit of a doubt as the evidence may admit. That’s not an absolute trust, mind you, only a willingness to consider the evidence in a light most favorable to him–but not to deny it entirely. And while there was a video of the event, I never viewed it myself, and so I cannot say for certain what actually happened. I only have his side of the story.

But you know who did view the video? The officer appointed, by Lausman, to preside over the summary court-martial. And that officer, the presiding officer, on reviewing all the evidence, including the video, concluded that the events depicted constituted an assault and battery by the petty officer upon the police officer, resulting in a guilty verdict and an award of punishment, but no discharge (but of course a summary court-martial cannot impose a sentence of discharge–that would need a special or general court-martial). However, in addition to the court-martial, Lausman saw fit convene an Administrative Separation Board, which can result in a discharge, and which, in this case, concluded that the petty officer, who had been in the Navy for some time and, again, would probably have made Chief Petty Officer within a year to two, should be discharged from the Navy with a less than honorable discharge.

And on its face, in light of the charges, that might even seem fair. Heck, if he hadn’t been in my division and such an upstanding individual otherwise, I’d probably have celebrated such an outcome. And I mean, like, literally celebrated. I experienced far too many instances of group punishment, including lockdowns where my entire ship was punished for the misconduct of an individual sailor and none of us allowed to leave until we completed “training,” often on the weekend, and always overnight, to get too bent out of shape when someone screws up in a major way and gets the book thrown at them individually instead of taking everyone else down with them. Heck, that’s that’s the way it should be: don’t punish everyone just for being assigned to the same ship as someone who did wrong, punish the wrong-doer themself. Fair.

But you know what doesn’t seem so fair to me? That Lausman, who, again, by the time of this incident had already (allegedly) committed a number of criminal acts related to corruption and bribery, now draws a full pension as a retired Captain in the US Navy, and he will continue to draw that pension for the rest of his life irrespective of whatever criminal acts he might have committed (to include one that he specifically pled guilty to).

Anyway, that all happened during the port visit to Australia around July 4, 2009. Reactor Department then spent the rest of the month dutifully pushing the ship through the water, maintaining the propulsion plant, and running drills and taking exams to prepare for our next major inspection. As for what the rest of the ship was doing, I haven’t a clue, but the next time we nukes were permitted to see daylight again, it was August and the ship was anchored out in Manila Bay.

2. Manila

It’s not uncommon for US Navy ships to have to anchor out rather than pull up to a pier, and particularly for nuclear-powered aircraft carriers–not only for their size, but to keep those reactors at a distance from densely populated areas outside the United States (you can imagine that not every country on Earth is super comfortable with another nation’s Navy rolling into the heart of a city or major port with two mobile nuclear reactors). But where they put us in Manila Bay? It was so far out you could barely see the city from the ship. For some perspective, here is a picture I took of Manila’s skyline from anchorage, with a security boat in the foreground and a couple of the strike group’s escorts (a destroy and a cruiser) in the middle-ground:

Where is Manila in that picture? It’s that thin line of darker gray way off in the distance, out on the horizon, only faintly visible through the haze. It’s not that it’s a small city without many tall buildings, it’s just that the carrier anchored out so far that even the tallest buildings were barely visible. By contrast, I have some later pictures from up close, once I finally got ashore:

See that? Like a proper city and everything. But from where they put us? Again, faintly visible through the haze as a line of darker gray out on the horizon. Worse, the liberty barge they put us on was some antiquated piece of junk which only made about five knots through the water, so it took over an hour to get ashore, and as an added bonus we were accompanied by only the faintest sea breeze, which also must have been going about five knots because the combined effect of the barge traveling with the wind was that the wind kept pace exactly with the barge going through the water, so it actually felt like there was no wind at all, and the exhaust from the barge’s (very noisy, very smoky) engines just hung around with us, becoming our very own smog-bank as we crawled through Manila Bay on a hot and humid day in August. It was the slowest and worst-maintained liberty boat I have ever been on, and, though I do not know for certain, I wouldn’t be shocked to learn that it was supplied by Leonard Glenn Francis’ own Glenn Defense Maritime (the defense contractor Lausman allegedly took bribes from, though of course his conviction was vacated as a condition of his plea to a lesser charge).

As far as where I went and what I did on liberty, here is what we (all of us, the entire ship) got to see of Manila apart from the skyline and the cab rides:

That’s it. A mall in Manila. I’m not sure which one exactly, but odds are 50/50 that it’s some part of the Mall of Asia, which was one of the two malls they allowed the entire carrier strike group to take liberty in, because otherwise they were worried about security (antiterrorism and force protection stuff).

On the plus side, the Mall of Asia is one of the largest malls in the world (I think it was touted as the seventh largest at the time?) and it actually was capable of accommodating a CVN, with its air wing, plus cruiser and destroyer escorts, without making much of a dent in terms of overall capacity. Manila is also the only place I ever visited where cheap, handcrafted items were available for purchase as souvenirs at a reasonable cost, rather than over-priced, mass-produced, factory-made items that the experienced traveler will note are essentially identical to those available in South Korea, Malaysia, Japan, Singapore, Australia, and even US territories such as Saipan and Guam. Truth be told, you could probably buy most of the items offered abroad as “local” souvenirs at your neighborhood Walmart Supercenter. Or, failing that, eBay. But the Philippines? That stuff was legit. I just wish I could have seen more of the country, or even just more of Manila.

However, some did not even get that sliver of Manila consisting of two malls and a taxi ride between them. And here I am not referring to sailors who were, like my petty officer from the Australia incident, on restriction–it pretty much goes without saying that on a ship of several thousand people, there were be a number of people on restriction at any given time. Rather, I am referring to those sailors who were euphemistically classified as “liberty risks.”

What is “liberty risk”? Well, the idea behind liberty risk is actually fairly straight forward: if a commanding officer determines that a service member under their command cannot be trusted to behave responsibly while overseas, then the commanding officer has the authority, by instruction (and good luck trying to find what instruction–it’s certainly not in the UCMJ), to limit the conditions under which that service member’s freedom of movement or “liberty.” Click here for a short article describing a liberty risk policy (albeit for the Marines) from around the time of this deployment (and note that while it does cite an instruction, it’s a fairly low-level instruction that gives no hint of whether there is any higher-level instruction authorizing the issuing commander to adopt such a policy in the first place).

Importantly, liberty risk, unlike restriction, is a purely administrative measure: it is not awarded through non-judicial punishment (Captain’s Mast) or court-martial, but is strictly a judgment call on the part of the commanding officer. One doesn’t even need to violate the UCMJ to be deemed a liberty risk: the commanding officer, acting on either the recommendation of subordinates or on their own, can simply make a determination that the service member in question cannot be trusted ashore, and so classify that service member as a liberty risk. Also unlike restriction, liberty risk can be of essentially indefinite duration. That is, whereas a commanding officer cannot sentence a service member to more than 60 days of restriction absent brining new charges for new violations of the UCMJ, there is no limit to the amount of time a commanding officer can put a service member on liberty risk, except that maybe, by instruction (if you can find the instruction to prove it, that is) the commanding officer might be required to periodically “reevaluate” an individual’s liberty risk classification–but note that “reevaluate” does not mean remove.

While not all liberty risk classifications amount to a total “curtailment” of liberty (by which I mean it is possible to be classified as a liberty risk, but still be allowed to go ashore subject only to certain conditions such as returning by a certain time or having a “liberty buddy” of a certain rank) the most severe form of liberty risk (what we called Class C Liberty Risk on George Washington–on my first ship it was Class D) could in fact prohibit a service member from leaving their military base or, if they happened to be a sailor assigned to a ship, from leaving their ship for so long as the ship remained overseas and they remained on liberty risk. How is this any different from restriction, apart from (1) being of potentially indefinite duration and (2) lacking even the scant due process protections of a non-judicial punishment proceeding? Well, as the ship’s legal officer helpfully explained it to me when I asked that very question on behalf of one of my sailors, the difference is that sailors on liberty risk don’t have to muster five times a day like the restricted personnel. Except of course that Lausman had decided that all sailors on liberty risk should muster, about ten feet away from the formation for the restricted personnel, a mere three times a day instead of five (although those three formations were held concurrent with or within minutes of three of the five restricted musters).

I want to be very clear on this: Lausman’s application of the liberty risk program was a gross abuse of authority. It was contrary to both the letter and the spirit of the fleet-level liberty risk instruction (which I did eventually track down) and was clearly calculated to circumvent the already scant protections afforded to service members under the UCMJ. As an example of just how arbitrarily and capriciously it was applied, consider that very often the sailors placed on liberty risk had done nothing wrong: it was just guilt by association. Recall, for example, the Australia incident in which one of my petty officers jumped out of a cab and abandoned his liberty buddy before managing to get himself arrested and ultimately court-martialed for assaulting a police officer. The liberty buddy in that situation did the only thing they could once the petty officer fled: they returned to the ship and reported the incident. Nevertheless, they were put on liberty risk for the rest of the deployment, and well into our return to homeport, all for merely having been present in the cab with the offending petty officer. And because our homeport of Yokosuka, Japan was itself an overseas location, that meant they spent those several weeks of post-deployment liberty risk on the ship just the same as if they were on restriction, even after we eventually returned to home port. In the end, they spent more time on the ship under the liberty risk classification than they would have if they had actually gone to mast, where the maximum amount of restriction that can be imposed upon a servicemember is 60 days. Or at least, that’s supposed to be the maximum amount of time a servicemember can spend on restriction. Naturally, Lausman had a way around that too: the policy–his policy–was that once a sailor got off restriction, they were immediately classified as a liberty risk, even if they had been put on restriction for something completely unrelated to their conduct ashore. We had, for example, another sailor who was taken to Mast and put on restriction for sleeping on watch. Terrible thing to do with a nuclear reactor, but also completely unrelated to their ability to conduct themselves ashore. All the same, Lausman transitioned them directly from restriction to Class C liberty risk.

Another way in which Lausman perverted the military justice system was more inventive. As previously noted, the maximum period of restriction permitted following Captain’s Mast is 60 days. However, if restriction is combined with extra duty (its own punishment under the UCMJ), then the maximum punishment is 45 days of restriction and 45 days of extra duty: the dreaded “forty-five and forty-five.” But Lausman? He figured out a way to give out 60 days of restriction (not counting the liberty risk that was bound to follow) and 60 days of extra duty at the same time. The way Lausman did it was by creating the so-called “OR” Division.

For those not familiar with how a ship’s divisions are designated, the first digit typically corresponds to the department, while the second corresponds to the division’s particular role. While not always a straight abbreviation (divisions within the supply department, for example, tend to be alphanumeric, eg: S1, S2, S5, etc), they very often are. My division, for example, Reactor Laboratories, was RL Division, while Reactor Mechanical Division was RM Division, and Reactor Controls Division was RC Division. But just what was “OR” Division? Well, normally O would stand for Operations, but here I am uncertain whether it was actually part of Operations Department, or if it was a part of any department at all–it might just have been floating off all on its own with whatever Senior Chief Lausman had assigned to lead it reporting directly to him. What was very clear, however, was that the R stood for Restricted. And so that’s what we called it: Restricted Division. The way it worked was that Lausman would sentenced a sailor to restriction-only at NJP (for the max–60 days), but then, immediately following NJP, transferred them to Restricted Division which, again, Lausman just made up. And what did sailors in Restricted Division do? Well, they chipped paint, mopped floors (oh, excuse me–swabbed decks!), and carried out assorted other low-level tasks: precisely the sort of tasks that sailors sentenced to extra duty would be expected to perform.

Needless to say, Lausman gained a reputation for being tough, but especially on nukes (who, again, he thought were overpaid and underworked, and what better way to remedy that than by taking nukes to Mast at the drop of a hat, knocking them down a paygrade, cutting their pay in half for a couple months, and assigning them to Extra Duty Restricted Division).

Anyway, next thing I remember, we were in Singapore.

3. Singapore

That was a lot of text, so here’s some nice pictures of Singapore to sooth things over:

Nice, huh? I’m really proud of the exposure I managed to get on that last one, and very grateful to… whatever that animal is for just staring straight ahead for so long. The Night Safari is pretty much obligatory when you visit Singapore.

Now, on the subject of Lausman, there’s really not much to say as far as the port visit to Singapore goes. In fact, the last two incidents I have to write about aren’t so much about Lausman as the effect he had on people. Take, for example, this one night in Singapore when I had duty as a Propulsion Plant Watch Officer. I won’t get into (classified) details, but the gist that is we had, in the other plant (remember, there are two of them on a CVN) a bit of a situation. Nothing dangerous–no one’s safety threatened–but a routine water sample indicated a much higher than expected concentration of a certain chemical in one of the propulsion plant systems. It might have been a problem with the sampling equipment, it might have been a problem with the plant itself, but it wasn’t. It was a problem with how this particular chemical was added to the system. Not that it shouldn’t have been added, only that it had been added in such a way that more of it ended up in the system than it should have, hence the higher than expected concentration. Such things do happen, and even the best of us make mistakes.

Except… knowing that such things do happen, and that even the best of us do make mistakes from time to time, by procedure, one of the first things that was supposed to happen after this chemical to the propulsion plant was to draw off a sample of water and check to make sure that the chemical had in fact been added appropriately. And unlike so many other samples, this particular sample was so easy to draw off and analyze that any idiot–heck, even I, the division officer–could have done it and known almost instantly that something had gone terribly wrong. But in this case the sample came back all good–at least according to the logs, which indicated that such a sample had indeed been taken as required, but showed no problem whatsoever.

Now, maybe this was because there was some problem with the sampling equipment (quickly ruled out by subsequent samples using a variety of methods and equipment from both plants, under the supervision of some of our most skilled ELTs), or maybe it was because the particular ELT who took and logged the original sample that even the freaking divo could do was a an idiot. An idiot who had managed to pass nuclear power school, nuclear prototype training, and qualify as an Engineering Laboratory Technician. Or, heck, maybe it was aliens! But it certainly wasn’t a brain fart: I mean, it’s certainly possible for a highly trained and capable individual to have a momentary lapse and forget to take a sample, but it’s not so easy to both forget to take a sample and somehow manage to make a log entry indicating that the sample was taken as required and everything was just fine: if he just forgot, then the log entry should have been missing, but it wasn’t.

There was, of course, one other possibility that had to be considered, and indeed there were whispers from some of the most knowledgeable and experienced ELTs that this was the most likely possibility: that this particular technician had willfully and knowingly omitted the sampling procedure to save time and simply fabricated the log entry. Because, after all, the chemical addition process itself was fairly simple, and barring a real bone-headed mistake it shouldn’t be possible to screw it up too badly. Except, as I have already allowed, otherwise trained and capable people do make mistakes, particularly when they’re tired or busy or otherwise distracted, which is why, after completing what is supposed to be the very simple process of adding this particular chemical to the system, you’re required by procedure to draw off a sample to double-check, just in case you suffered such a momentary lapse.

See, I get it: even good people make mistakes, so procedures are in place to help catch such mistakes early. Unfortunately, as the prevailing view among certain of our most knowledgeable and experienced ELTs went, this particular ELT maybe didn’t “get it,” and so, maybe–because he never imagined that he could make such a simple mistake–he added the chemical, but skipped the sample to save himself some time, leaving it for the next technician to come on watch and discover the problem on her own some hours later, by which time the chemical had made its way much further into the system and reached much higher concentrations than it would have if the mistake had been caught sooner. In other words, according to some of our most knowledgeable and experienced ELTs, the first ELT, the one who added the chemical had (1) made a bone-headed but eminently forgivable mistake, perhaps due to being tired or distracted, but then (2) flagrantly lied about taking the required sample that would have caught his own mistake quickly, and falsified his logs accordingly to indicate a sample had been taken and everything was normal when in fact it was not.

But that was not what happened. Or at least, that’s not the story we went with. See, there was a finding of fact, made by my immediate superior and endorsed by the Reactor Officer, that it really was just a mistake. See, this highly trained nuclear engineering laboratory technician, whose level of knowledge and skill was shown to be more than adequate through a number of practical and written examination administered both before and after the incident, must have both made a mistake in adding the chemical to the system and then made a second, compounding, mistake in drawing off the very easy to take and analyze sample that, by sheer, coincidence prevented him from detecting his first error. Another comedy of errors!

Of course it was mentioned, as I was having a spirited conversation with my immediate superior, that a factor in arriving at this particular finding of fact–contrary to the suggestions of some of our most knowledgeable and experienced ELTs–that things might not go so well for the Department if we went with the alternative explanation (the one preferred by those most knowledgeable and experienced ELTs) and reported to Lausman that one of our ELTs had knowingly and willfully falsified a propulsion plant log entry. I mean, sure, the ELT who (under this alternative, non-preferred hypothesis) lied about taking a sample and then gundecked his logs would be severely punished (all well and good), but that was hardly the point.

Left to their own devices, with exclusive decision-making authority, I strongly suspect that both my immediate superior and the Reactor Officer would have been just fine with such an outcome: gundecking of any sort is a serious offense, but for someone entrusted with performing radiation surveys and taking chemical samples that relate to the safety of not one, but two nuclear reactors, to gundeck a chemical sample like this is arguably among the most serious of offenses–worse even than cheating on an exam (and recall what I wrote upthread about people who get caught cheating on exams in the nuclear Navy). No, my immediate superior’s concern–and I suspect the Reactor Officer’s too–was what Lausman might do to the rest of the division, or even the rest of the department, if we went with the explanation that our most experienced and knowledgeable ELTs had put forward: that this was a minor lapse in procedure, followed by a a gross and willful lapse in integrity relating to the safety of the nuclear propulsion plant. It was well-established by this point that Lausman hated nukes and had only just been held back from coming down hard on the department for suffering merely average performance to exist, and it was in that context that the decision was made to keep this incident at the departmental level by ascribing it to a series of unfortunate events, consisting of two highly improbably but equally honest mistakes leading to having an abnormally high concentration of a particular chemical in one particular system, and nothing more. Certainly not willful misconduct. That meant we could deal with it internally, at the departmental level, through “upgrades” to the sailor’s “Level of Knowledge” via additional “training.” No need for Lausman to be involved.

Such was the effect Lausman had on “good order and discipline” under his command. When standard performed is substandard and substandard performance is not permitted to exist, things don’t all uniformly become “excellent,” it’s just that certain things tend to get swept under the rug.

4. Hong Kong

Singapore was the last port visit of USS George Washington‘s 2009 Summer Cruise. We returned directly to our homeport of Yokosuka, Japan (where, again, many members of the crew who had either committed no crime or had at least served out their sentences were euphemistically classified as “liberty risks” and still not permitted to go ashore, even though they had homes and sometimes even families waiting for them, because we were still technically “overseas”) and spent the month of September performing maintenance and upkeep. By early October, we were underway again for the somewhat misnamed Winter Cruise (we’d be back by Christmas, so it was really more of a Fall Cruise).

On the nuke side of things, we had a pretty major inspection towards the end of October. It was what all our training had been leading up to. We did well enough on it that those of us not still on liberty risk from the Summer Cruise were allowed to enjoy Honk Kong, where we arrived the same day we got our results for the inspection.

Uncommonly dedicated readers may recall that I just barely missed a port visit to Hong Kong during my second deployment, aboard USS John S. McCain in 2006. So naturally, having waited three years, I was eager to finally go ashore there. But I’ve gotten ahead of myself. I promised one more Lausman story, and as it happens, the Lausman story for this port visit actually happened as we were getting underway from Yokosuka.

As with the preceding story, Lausman himself isn’t so much a character here as a kind of force. A malevolent force that permeated throughout the entire ship, being felt through the bulkheads and the deckplates, weighing at all times upon the minds of its crew, and eroding good order and discipline at all levels of the chain of command. The inciting incident this time around was simple enough: yet again, one of my petty officers had screwed up, arriving several hours late to work–which, normally, as an isolated incident, with no aggravating factors (she wasn’t drunk, just overslept) wouldn’t be that big a deal. Except, in this case, she wasn’t just several hours late showing up to work, she was several hours late showing up on the morning the ship was due to get underway. In fact, she appeared on the pier mere moments before the ship’s brow was to be removed by a crane, which would have made it quite impossible for her to come aboard. Thus, she was not only several hours late to work: she was mere moments from missing ship’s movement (which, for those unaware, is a sufficiently grave offense as to warrant its own UCMJ article right alongside–I kid you not–“Jumping From Vessel Into the Water”). But, sometimes mere moments make all the difference, and here she made it aboard just in time, removing the situation from a grave offense on the level of a felony to a mere misprision.

On any other ship, such a matter would surely have been dealt with by a strong talking to from a Disciplinary Review Board made up of Chief Petty Officers with some Extra Military Instruction (busy work) thrown in for good measure. Or, maybe, just to make a point, a stern a finger-wagging from the ship’s second in command at Executive Officer’s Inquiry (XOI). And you know what? That’s pretty much what happened here. The unusual thing wasn’t what happened, but how it happened, and I mean specifically the XO’s candor at XOI. I mean, normally, an XO will assert confidently that he or she is making the right decision on their own authority (a real “Damn Exec” kind of thing), whether that be, as here, to dispense with things at XOI or, alternatively, to refer the matter to the Captain with a recommendation for Captain’s Mast. But here? Here the XO as much as said (paraphrasing) “I have to come down as hard on you as I can to save you from the Captain, because if the Captain gets you, he will ruin your life.” Not “I am coming down hard on you because that is what this situation warrants” or even “You’re lucky I’m such a nice guy that I’m not sending you to Mast even though that’s totally what you deserve,” but, in essence, “I have to… because… the Captain.” I guess the takeaway here is, it’s hard to own orders when the people giving them suck, and harder still when the man with the sheriff’s badge is (according to what I consider credible allegations detailed in the US Department of Justice’s original indictment and as supported by a fair amount of evidence introduced at trial) a corrupt asshole. That’s it. Pretty simple, really.

Now, before we proceed onto Hong Kong, I want to offer a few words in defense of the sailors of my division. I have, in casting light on a most despicable subject (one David A. Lausman, formerly of Commanding Officer of USS George Washington, and for some time also–according to what I consider credible allegations–in the pocket of one Leonard Francis), likewise shed some light on certain other individuals who, in spite of their shortcomings and even their misconduct, gave mostly honorable service, and in any event did nothing like the kind of damage to good order and discipline, and by extension the combat power, of USS George Washington and our nation’s Navy, than did Mr. Lausman (and that’s even if every allegation the DOJ made was false and he is in fact completely innocent of any crime: just knowing what I know about him from personal encounters and having had the displeasure of serving under his command, I can say with confidence that he was toxic and unfit to command).

But I digress. Here, what I wanted to say, what I will say, is I had a great division. Simply amazing. And for what it’s worth, so was my chain of command within Reactor Department, up to and including the Reactor Officer: they really cared about the wellbeing of all of the sailors under their command, myself included, in a way I just was not accustomed to coming off my first ship. The ELTs I got to work with were easily among the most talented, the most dedicated individuals I have ever worked with, inside or outside of the Navy, and I was particularly fortunate to have a couple of really excellent leading chief petty officers throughout my time in the division. Though I still cringe to recall that Lausman, of all people, lead me through the oath of office when I assumed the rank of Lieutenant, I am proud to have had then-Chief Petty Officer Jeremy Douglas pin the bars on me.

With that out of the way, here’s some pictures of Hong Kong from that narrow slice of time between when the British give it up and the Chinese government reneged on its “one country, two systems” promise:

So that was Hong Kong. My last port visit of the deployment and my last port visit ever in the western Pacific. But not, oddly enough, my last port visit aboard USS George Washington. Perhaps I’ll get around to that, in time…

From Here to Eternity

I’ve never been a fan of “classical” Hollywood. I can’t say why–I’m no film critic–I just don’t care for most of the much beloved (by others) “classics” of the era. If I had to try and take a stab, though, I’d say it’s probably that I don’t I don’t like how black and white the heroes and villains are. I mean, I can do with black and white photography, but not people–we’re too complicated for that.

Just the same, I do like The Caine Mutiny enough to regularly drop references to it in my posts, and I like Mr. Roberts (though I can’t recall if I’ve ever mentioned it before). And I suppose one reason I like those is films is that the characters–the principals, anyway–are complicated. We don’t just see good people doing good things to overcome bad people doing bad things: we get to see the friction that tends to keep good people from doing good things, and not just because “the big bad” is so bad, but because it’s actually kind of hard to do, let alone to be, “good.” We might even have cause to question what exactly it means to be “good,” and how, if ever, it might be distinguishable from doing “good.” In The Caine Mutiny, for example, we get to ponder whether the “good” people have really done such a “good” thing in the end–certainly they could have handled things better. Such complexity doesn’t just make the story more interesting: it makes it possible to identify and sympathize with the “heroes” without feeling judged, seeing how their own desires to do the right thing are tempered by their failings, just as we will too may fail. Because even when the “right” thing to do is clear enough, sometimes it’s damn hard to do it, and on top of that it’s not always so clear what “right” looks like to begin with.

And then there’s From Here to Eternity. It, also, is an exception to my general disdain for classical Hollywood, but I wouldn’t put it in the same category as The Caine Mutiny or Mr. Roberts. I’ve only seen it once (it was just good enough for a first-watch, but not for a re-watch) so I don’t know it as well as those other two films. It’s set in Pearl Harbor in 1941 (which should be sounding some alarms) and, if memory serves, the plot revolves around a soldier/ex-boxer who doesn’t want to box anymore for some deeply held moral reason; a commanding officer who wants to make him box because, if he does, he’s sure to win the division boxing competition and that, somehow, would make this commanding officer look good, and maybe even help him earn a promotion; and a First Sergeant who wants to be a good NCO on the one hand, but is, on the other hand, having an affair with the wife of his commanding officer (the very same commanding officer–but it’s okay, because this commanding officer is a real Lausman: toxic as hell and not above abusing his authority to coerce his subordinates into doing what he wants, using them for his own selfish ends, destroying unit morale and eroding good order and discipline in the process). All in all, it’s the sort of straight-forward, uncomplicated story that I’ve come to expect from classical Hollywood, right down to having such little faith in its own main storyline that it feels compelled to inject a completely unnecessary love triangle in a (to me) fruitless attempt to keep the audience’s attention and (more successfully) pad the runtime.

So why do I still give From Here to Eternity a pass, even as it seems afflicted with all the worst elements of classical Hollywood? I suppose it’s because of how its interpersonal conflicts pay off: that is, they don’t, and I kind of feel like that was the point. Like, maybe it’s not an accident that these characters’ disputes seem so utterly inconsequential to me: it’s just possible that they were actually written like that on purpose. Because the resolution, to the extent there is one, is that (spoiler!) the Japanese bomb Pearl Harbor, and it turns out none of that nonsense really matters in the end–or at least things turn out that it would have been better for all involved if such things hadn’t mattered to them in the first place. It’s all just swept away as what the audience, watching from the post-war era, must have known was coming finally arrives, even as the characters, engrossed in their own lives, relegated to a time before the war, couldn’t possibly have anticipated–not fully, anyway. But, here again, one of the film’s apparent shortcomings becomes a strength: by the time bombs start falling, the story has dragged on for so long that the Japanese attack actually comes as a surprise, even to the audience (or it did to me, anyway–albeit perhaps too welcome of a surprise).

And so it was that after returning to Yokosuka, Japan with George Washington in December of 2009, after a series of short cruises that seemed to last forever, I set myself to studying for my Prospective Nuclear Engineering Officer’s exam–which all nuclear-qualified line officers, both surface and submarine, are required to take (and pass, if they want to remain nuclear-qualified officers) towards the end of their nuclear division officer tour. I spent several months consumed with that task, to include several weeks spent in San Diego studying for and taking the written portion of the exam, followed by a brief trip to DC for the oral exam. That all took me to July of 2010.

By the time I returned to Yokosuka, USS George Washington was underway again for the start of its 2010 Summer Cruise. Although I flew out on a C-2 Greyhound to meet it, I would not share in any of its port visits that year. After only two days, I packed once more into the back of a C-2 Greyhound and was catapulted off for my next assignment. My orders, upon detaching from USS George Washington, were to proceed to Expeditionary Combat Readiness Center, Norfolk, Virginia, then report to the Navy Mobilization and Processing Station for five days, followed by three weeks of Navy Individual Augmentee Combat Training at Camp McCrady in South Carolina, after which I would deploy to Iraq.

End Notes

- In an earlier draft of this post, I made it a point, throughout, to refer to Lausman as “Convicted Federal Felon Lausman,” and then, once the felony convictions were thrown out due to prosecutorial misconduct and he was instead allowed to plead guilty to a single misdemeanor in exchange for a slap on the wrist, as “Confessed Criminal Lausman.” But then I realized that lots of people run afoul of the criminal justice system and, even among the genuinely guilty, they’re not all bad people. They might (or might not!) have done a bad thing, but that hardly makes them irredeemable, and they don’t deserve to be lumped in with a man like Lausman anymore than the vast majority of naval officers do (myself included). Because, at base, what makes Lausman worthy of shame and degradation isn’t his conviction, or even the fact that he did a bad thing, it’s his hypocrisy and his toxicity. His whole course of conduct is its own insult: not to himself, but to every sailor who was ever subjected to his “leadership,” and to every taxpayer whose honest labor was taxed and thus contributed to his salary, and which contributes still to his full pension as a retired US Navy Captain. He is a disgrace irrespective of his criminal status. While I’m not generally a fan of cashiering, I’d happily make an exception in Lausman’s case: he should be publicly shamed and degraded. All the punishments he imposed at Captain’s Mast should be set aside, and any adverse outcomes arising from the courts-martial or administrative separation boards he convened should be subject to review on the bases of impropriety and inequity, with a presumption in favor of appellants in light of Lausman’s gross deviations from what is expected of a Commanding Officer.

- Captain Graf, as in the Captain who was somewhat infamously relieved of command of USS Cowpens for “cruelty and maltreatment” and “conduct unbecoming an officer.” That Captain Graf. I (almost literally) ran into Captain Graf around the same time as I met Lausman (relatively speaking, keeping in mind this was all over a decade ago–it was actually a few months before Lausman took command). It was only the briefest of encounters. I was on the O3 Level–that is the deck just below the flight deck on a Nimitz-class carrier like GW–and she was coming through a curtain that separated the “blue tile area” (where the strike group commander, a Rear Admiral, and his staff worked) from the rest of the level (where us peons could walk freely). It was a narrow passageway, and so, on seeing this unfamiliar O-6 coming through the curtain, I instinctively moved aside, put my back to the outboard bulkhead, and came to attention (as is appropriate when an O-2 encounters an O-6 in a narrow passageway). Captain Graf, for her part, paused briefly as I moved aside, smiled, and said “Oh, thank you!” before slipping past. We each went on our separate ways, and that was that. In other words, it was completely unremarkable, and whatever she might have done aboard Cowpens, she at least could manage to be civil in close proximity to an unfamiliar junior officer for five whole seconds. Which is a damn spot more than I can say about Mr. Lausman, and I have at times wondered how it is that the same Admiral who saw fit to relieve her (rightly, of course, in light of her conduct aboard Cowpens), but took know action against Lausman, even as he was stinking up the place right under the Admiral’s nose. And of course Captain Graf, unlike Mr. Lausman, doubtless had to deal with a fair amount of adversity coming up in the Navy. In truth, I only remember the encounter because it was so unusual to see a female O-6 with a SWO pin and command badge, considering that it was only in 1994 that women were allowed to serve on surface combatants like Cowpens and George Washington. Further, coming up as she did in an environment where sexism was codified into law, it’s just possible that Captain Graf didn’t have the same range of opportunities to become her best self as someone like, say, Lausman would have had at around the same time. I make note of that not to excuse Captain Graf’s conduct aboard Cowpens–I’ve read the investigation and it’s a doozy–but rather to emphasize just how outrageous Lausman’s behavior was by comparison, having, throughout his career, been unencumbered by any such institutionalized prejudice. And while what Captain Graf did to her wardroom was terrible, I do believe that the corruption that Lausman engaged in, as described in the credible allegations contained in the DOJ’s original indictment, had much more far-reaching and deleterious effects upon the Navy as a whole. And then, on top of all that, it just so happens that Lausman was also, like Captain Graf, a toxic leader, except he was put in charge of a much larger warship, with a lot more people made to suffer under him, over a much longer period of time. And that will remain true even if there exists incontrovertible evidence that he is actually innocent of any and all charges of corruption, even if it turns out he never met Leonard Francis (although the Washington Post does have a pretty good picture of him looking chummy with Leonard Francis).

- On the subject of variations between ships of the same class, consider, for example, that USS Nimitz was laid down some time during the Vietnam War and commissioned on May 3, 1975–long before I was born–while USS George H. W. Bush, also a Nimitz-class carrier, was commissioned January 10, 2009–roughly contemporaneous with the events of this blog post. Not only was Bush designed with considerable differences based on technology not available when Nimitz (or for that matter, George Washington) was laid down, but Nimitz itself has been and continues to be (it’s still in service as of posting) the benefactor of numerous upgrades and modifications throughout its service life. Every ship is. And yet, not every ship, even two theoretical ships launched and commissioned at roughly the same time (as no two US Navy aircraft carrier have been since probably WWII), will have those upgrades installed at the same time. What this means is that at least some of the equipment on any given ship is bound to be different from equipment fulfilling a similar or identical function on literally every other ship, even of the same class. So how do you ensure that the training program for each individual ship is properly tailored to the equipment and procedures relevant to that ship? Well, one way to do it–a really terrible way to do it, in my opinion–is to demand that each individual ship develop its own training program effectively from scratch, subject only to certain guidelines put forward by higher authority. As each Jedi must forge their own lightsaber, so too must each Reactor Training Assistant craft their own training program. Again, it sucks.

One thought on “Retrospective 3”